Written by Jack Bettar

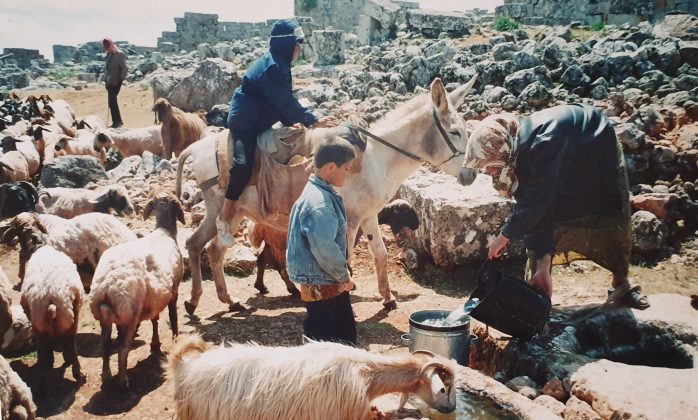

Spread across fertile mountains, between olive and pistachio groves, and across windswept limestone hills, sits an assortment of ancient ruins, some mysterious, but all precious not just to Syria’s history but to the history of humankind in general.

In the Aleppo and Idlib governorates (provinces), there can be found unique and rare insights into life more than fifteen hundred years ago and perhaps the world’s finest repository of Byzantine churches and monasteries to be discovered.

Image: The Basilica at Qalb Lozeh. Image from Wikipedia.

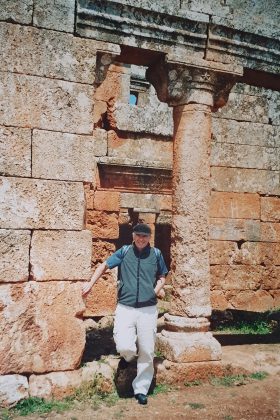

It was in Idlib, specifically in the dusty roadside town of Qalb Lozeh (translated as ‘Heart of Almonds’), that the architectural inspiration for the world’s most iconic and resplendent cathedral, Notre Dame de Paris, came. Though partially ruined, the basilica, constructed of local limestone in the mid-5th century, still stands in all its glory, atop a hillside.

Any visitor to Paris will forever recall the iconic twin-towered façade, the feature that separates Notre Dame from its contemporaries, but few will know that the first church to boast this grandiose design was the Basilica of Qalb Lozeh in Idlib. It was also this church which was an ‘ancestor’ of other great gothic cathedrals of Europe.

Its extravagant arched narthex welcomed thousands of pilgrims from across the Fertile Crescent and beyond, many of them on their journey to hear an eccentric and devout hermit Saint Simeon preach as he sat atop a pillar for over 30 years, in the very spot where a church, commissioned by Byzantine Emperor Zeno, would be erected in his honour.

A striking sense of beauty leaves a visitor to Saint Simeon Stylites Church in amazement. For centuries, the over 5,000 square metre complex of Saint Simeon’s Church, constructed in the 5th century after the Saint’s death, encompassed four basilicas, a monastery, accommodation, two minor churches and a walk-in baptistery, making it the most outstanding and largest church of its day, not surpassed in all of Christendom until the construction of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Unlike the Hagia Sophia, Saint Simeon’s Church, in today’s Aleppo governorate, was constructed on a hillside tens of kilometres from the nearest town. The crucifix-shaped church enshrined the column of Saint Simeon in the centre, where it still stands. For several centuries, pilgrims would come to the church and chip away at the column, leaving only a stub.

Although common belief places the roots of the Maronite rite in Lebanon, a 30-minute drive from Saint Simeon’s Church takes you to the ruins of Brad. Here, the Patron Saint Maroun was born and is buried. The modest tomb makes up a much larger complex including the Julianos Church, built in the late 4th to early 5th century, only a few years before Saint Maroun passed away and before Qalb Lozeh was built. The Maronite history in Lebanon did not begin until many centuries after.

Julianos Church, the Basilica of Qalb Lozeh, Saint Simeon’s Church and the ruins of other Byzantine churches are located in an area classified in 2011 by UNESCO as ‘The Dead Cities of Northern Syria’.

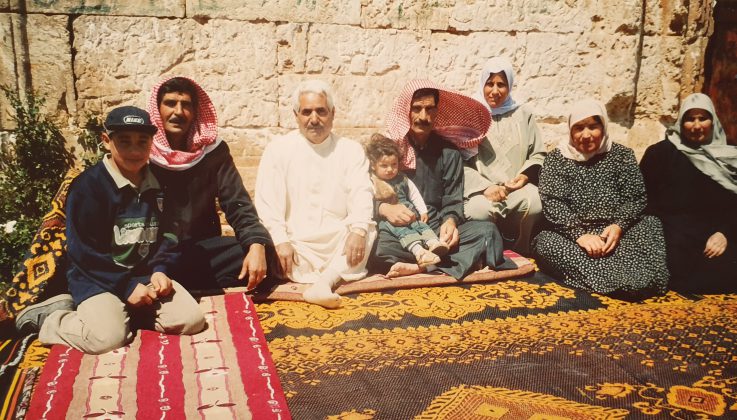

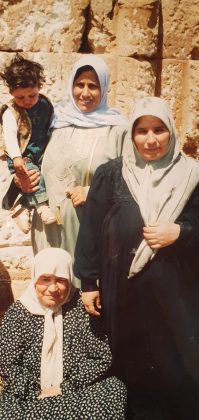

Apart from the impressive ruins mentioned above, hundreds of less notable sites in the Dead Cities that are remarkably preserved give insight into ancient life through the existence of villas, wine presses, public baths along with olive presses and mills. These villages give an exceptional illustration of the widespread development of Christianity in Syria and the Near East and an incomparable demonstration of the lifestyles and cultural practices of these rural civilisations.

The most well-known villages are Serjilla and Bara on Jebel Riha. In Bara, a settlement that once must have been surrounded by vineyards and olive groves, rise conspicuous pyramidal burial tombs and sarcophagi which are unique only to this Dead City.

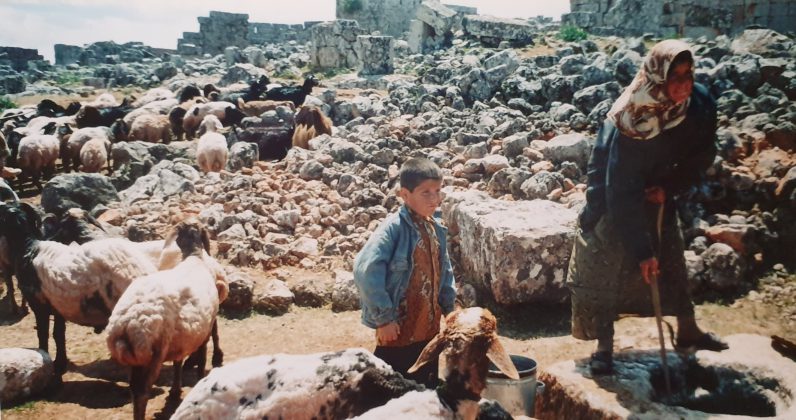

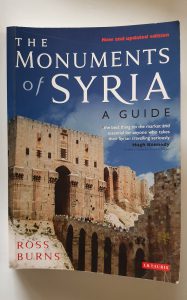

Ross Burns, a former Australian ambassador and author of ‘The Monuments of Syria: A Guide’, writes that the Dead Cities are ‘a great archaeological puzzle’.  Readers are encouraged to probe this mystery. Burns writes that by the tenth century the region was deserted; it was ‘a frontier zone between the Byzantines and Arabs’.

Readers are encouraged to probe this mystery. Burns writes that by the tenth century the region was deserted; it was ‘a frontier zone between the Byzantines and Arabs’.

So over time the merchant routes were discontinued and agrarian towns such as Serjilla, which thrived on trade, melted away into the now-barren landscape, leaving behind slowly fading physical testimony to the magnificence of these sites in their prime years.

As these towns sit in the backdrop of two provinces that have made front-page headlines, they are a reminder to the former glory of this region, their significance and influence on the world. One can feel the power of the limestone walls and though an eerie quality permeates due to a lack of tourists, they still retain their romantic appeal and splendour.

The author of this article, Jack Bettar, is a student from Sydney, Australia, who has a keen passion for history and writing.  He has had numerous articles about early Syrian migration to Sydney published. He has also recorded oral histories of Syrian migrants as a way of preserving both individual and communal experiences. He is currently curating a permanent archival exhibition that will celebrate the 125 year history of the Melkite Catholic Church in Australia. Jack is also a passionate musician, playing classical, contemporary and Arabic music. He was invited to perform at the Great Hall of Sydney University in 2015.

He has had numerous articles about early Syrian migration to Sydney published. He has also recorded oral histories of Syrian migrants as a way of preserving both individual and communal experiences. He is currently curating a permanent archival exhibition that will celebrate the 125 year history of the Melkite Catholic Church in Australia. Jack is also a passionate musician, playing classical, contemporary and Arabic music. He was invited to perform at the Great Hall of Sydney University in 2015.

For further information,

In war-torn Syria’s Qalb Lozeh village, this church that ‘inspired Notre Dame Cathedral’ still stands, published in South China Morning Post, 20 April 2019

Below are mosaics from the period discussed in the article. They are from a church in Syria’s Hama governorate, which borders Idlib and Aleppo.