Published by Beloved Syria with the permission of the author.

‘A Child in Damascus’ was first published in SYRIA through writers’ eyes, Edited by Marius Kociejowski (Eland Publishing Ltd, 2010)

A Child in Damascus

by Josceline Dimbleby

…years later I understood the saying that once you have lived in Damascus, it lives in you

In the early summer of 1950, aged seven, I arrived in Beirut after a rough sea voyage from England on a small cargo ship, the Henzee. I was on my way to Damascus to join my mother and my stepfather, who had just been posted as Minister to the British Legation in Syria. Accompanying me was a formidable woman with a large beak of a nose and grey hair cropped like man; Mrs Rydon was to be my governess as there was no English school in Damascus. I was clutching Alice, my yellow-haired rag doll, and Little Mut, a miniature bear with an endearing expression who I had picked up on the street outside of Harrods in London; I could not have gone anywhere without these two. My mother, Barbara, and my stepfather Bill, had travelled ahead by the much talked about new aeroplane, the Pan American Airways ‘Constellation’, a great lion of the sky which conveniently flew from England via Rome to Damascus. My mother was surprised that it was warm enough in the plane not to have to wear an overcoat. Travelling with them were Dudley, my stepfather’s adored Siamese cat, and Eustace, a Maltese terrier who was soon to expire in the Damascus heat.

I could see my mother and Bill waiting on the quay. I was introduced to the Legation chauffeur Shafiq, a slim, handsome young man with green eyes, dressed in a khaki uniform and driver’s cap. In the official diplomatic car, a black Humber Hawk, Shafiq drove us out of Beirut and up over the stony Anti-Lebanon mountains into a beautiful and verdant valley, the Bekaa, rich with crops and fruit trees. After the frontier the country became barren once more, dotted with craggy rocks and a few cattle. As we came down a steep slope we passed one of the large American cars used as share taxis, crammed with passengers, at a standstill on the way up; its engine was boiling and the driver had cut a water melon in half and put it on the radiator to cool it down.

At the frontier Bill expected to be waved through in his official diplomat’s car which flew the Union Jack on its bonnet, but clearly the border guard that day was suspicious. Sharply, he asked Bill to produce his papers, and frowning, took them into his hut. A few minutes later he emerged with another guard. They both smiled broadly as the first guard returned Bill’s papers. ‘Drive on Sir Wizir Bollock’ the second guard said, with a theatrical sweeping gesture. Bill’s double-barrelled surname, Montagu-Pollock, was funny enough; we used to tease him that it sounded just like Carlton-Browne of the FO.

A stream which had started up in the bare mountains became fringed with green and when the road entered a dramatic gorge I realised that what had been a stream was now a river, flowing swiftly beside us on our right. This was the Barada, known as ‘the lifeblood of Damascus’, the creator of the oasis the city was built within. We emerged from the gorge and drove to a high point where we got out of the hot car to a wonderfully cooling wind. A magical sight greeted us in the sun-bleached desert below; here was Damascus, famously known as the oldest continuously inhabited city on earth. The Prophet Muhammad, seeing it as I was from the desert, found it so beautiful that he would not visit it because he felt it would be wrong to anticipate the joys of Paradise, even though it was a Christian city at that time. Now I was going to live in this paradise. With its story book domes and minarets Damascus nestled in its famous oasis, known as the Ghouta, where I could see waving poplars and sycamores, shimmering as their leaves moved in the sunlight. Narrow sparkling streams appeared to run everywhere, criss-crossing countless fruit orchards. This unexpected greenery was encircled completely by the yellow desert hills.

As the car descended from the hills we entered the most foreign-looking place I’d ever seen. For the first time I heard the muezzin’s cry from the minarets. There was no electrical amplification then and the beautiful, haunting sound captivated me. We drove into the city along a wide street. We seemed to be almost the only car, but there were trams and horse-drawn vehicles – an incongruous mix. There were hardly any women around and the few I noticed hurried along, mostly with veiled faces, black waist length capes over their heads and long black skirts. Plenty of men stood in the street talking or sat in cafes smoking hubble-bubble pipes; they wore Turkish style red fezes with black tassels, and extraordinary dark blue or black trousers, baggy and capacious, but tight around the ankles. When I asked my mother about these she smiled and said they were called cheroual, explaining to my great surprise that they were baggy because it was thought that the second Messiah would be born to a man, so the men wanted to be ready for childbirth.

At the start of the 1950s, with the Syrian people experiencing independence for the first time, there was a feeling of excitement and tentative hope but also, as ever, uncertainty. The last of the French troops had been forced to move out of Damascus by Syrian nationalists aided by British pressure in April 1946. But after centuries of colonisation independence did not come easily. The republican government formed under the French Mandate was overthrown in 1949 by Colonel Adib Shishakli who had been an officer under the French; a series of military coups and the assassination of successive presidents followed. A few months after our arrival Shishakli seized total power that lasted, tenuously, during our years there, creating a comparatively more stable period when ordinary people got on with their daily lives.

As a seven-year-old, apart from becoming quite used to hearing distant gunfire, I knew nothing of the political situation. To me the excitement of being in Syria was that this was the Holy Land. Although I grew up to be what my children jokingly called ‘a heathen’ I loved Bible stories as a young child and always did well in Divinity lessons. And Damascus did not only bring those stories to life; it also had an Arabian Nights magic about it; you could see it in the covered alleyways of the market, the great al-Hamadiye souk, where gold jewellery and silk brocade shimmered in the half-light, in the elegant minarets of the mosques, in the trickling fountains, mosaic floors and graceful arches of courtyards in the old houses, in the ancient Umayyad mosque and in the clear night sky of the desert, like midnight-blue enamel decorated with a silver crescent moon and flashing stars. Damascus had exotic beauty, drama, danger and mystery. At the time it still looked like a place of great antiquity; you could see signs of its complex, turbulent history all around you. It seemed like a city that the modern world had not yet discovered.

‘Damascus catches your heart’

I was entranced by my new life in this very different place and years later I understood the saying that once you have lived in Damascus, it lives in you. Those early days in Syria became the most vivid and surviving memories of my childhood. Recently I re-met, after more than fifty years, an old man, near to death, who we had known in Damascus at the start of the 1950s. He had lived in many other countries since but he told me he had never felt the same about anywhere else; his pale eyes moistened and he sighed: ‘Damascus catches your heart’.

The British Legation residence was a lovely house, dating back to the Turkish era of the late 19th century. It was on University Street, which ran from the Hijaz railway station to the university, in the Halbouny area of the city, which had been developed as a smart residential area at the beginning of the 20th century. The streets here were paved evenly with new cobbles, unlike the timeworn cobbles in the old city, which tripped you up. The residence looked spacious, light and welcoming, even though I was at first alarmed by the shouts of a mad woman by the gates, who was surrounded by a group of women beggars and several ragged children. These women and children were always there, including the harmless mad woman, sitting against the wall, and with time I almost felt they were part of the household. Next to the beggars was a sentry-box where one of our armed night guards used to sit; on a moonless night a few months later one guard mistook the other for an intruder, and shot him dead, but nobody treated the incident as very important. I was always in bed by the time the guards arrived and was surprised to learn there were any.

The house was wide and two storied, topped by an ornamental balustrade. the walls had been painted white, and the windows had dark turquoise blue shutters. Set a little above the street, tall metal gates followed by a steep stone stairway led up to a central front door. On the street side the windows looked onto the perfect little domes of an old Turkish mosque, Tekkiye Suleymaniye, with the Barada River, the verdant orchards of the Ghouta, and the bleached desert mountains beyond.

The first thing you noticed as you stepped inside the house was how cool it was; in fact a very thick roof was the reason that even in mid-summer the rooms never got hot. In characteristically Arab style the ground and first floors were mainly taken up by a ballroom-sized reception room stretching from front to back, with smaller rooms on both sides. The floors of the reception rooms were marble; wooden pillars on the ground floor supported the floor above, which trembled as you walked across it. Bill was told that it was dangerous to have more than twenty people at one time on this upper floor but as he was what must have been one of the least conformist of English diplomats, with natural urges to be disobedient and foolhardy, he continued to hold large parties up there. At the back of the house two pairs of double doors opened onto a wide terrace and, I soon discovered, a large garden full of delights.

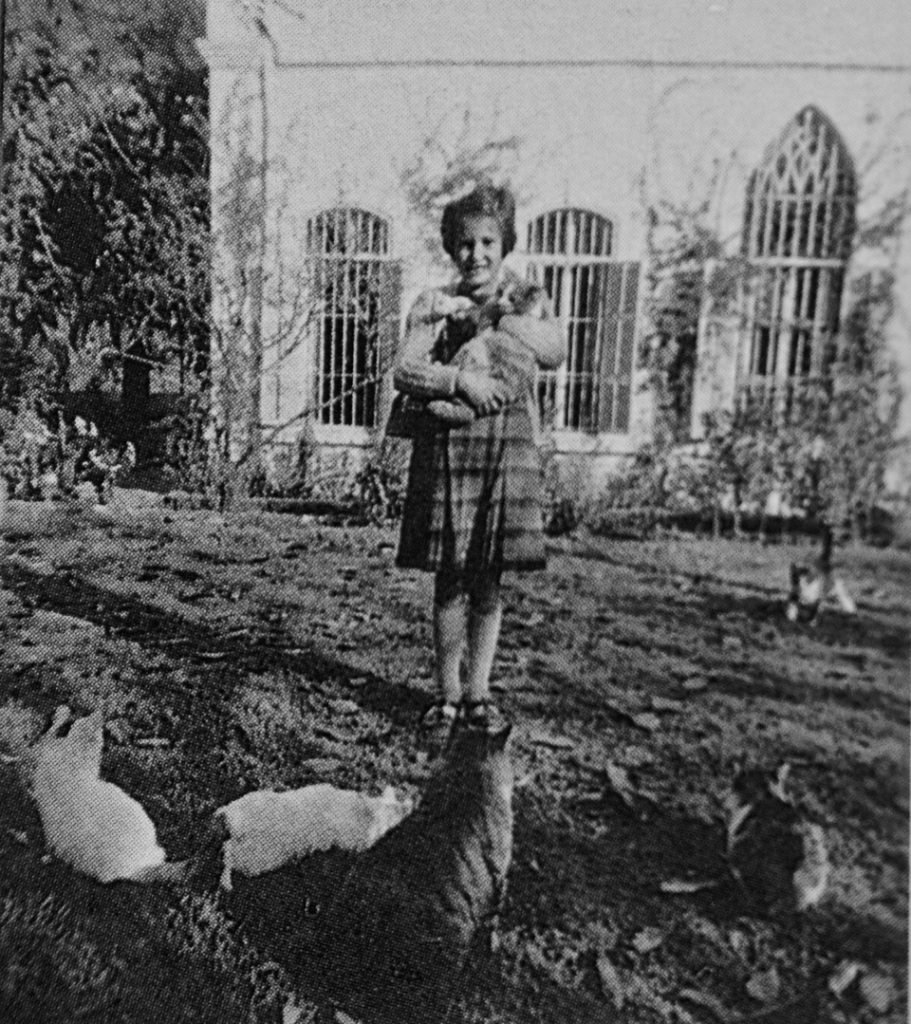

There were paved paths and lawns, and an orchard at the far end with olive, lemon and little mulberry trees. Criss-crossing the whole of the garden were narrow irrigation streams, so that everything was a fresh green and the famous scented Damas roses continued to flower despite the dry summer heat. In the middle of the lawn was a statuesque old walnut tree; as the sun shone fiercely down the contorted branches made dramatic shadows on the velvety carpet of green beneath. Steps from the terrace led up to a long arched tunnel with vines and flowering creepers climbing over it, creating a shady walkway to a wider area where the grownups would sit under a pergola. At the far end of the garden, in a small mud building, the gardener lived with his wife, eight children and a sheep. Two of the children were to become my constant playmates when I was in the garden; Nowall, who was my age, and her younger brother Farouk, who was dressed in skirts as was still the custom for little Arab boys.

Outside my ground floor bedroom on one side of the house was a fountain surrounded by a circular pool. After our hot journey from Beirut on my first day I stripped down to my underpants and sat in it to cool down; the water reached my shoulders and the fountain spattered over me. Wide leaves of a large mulberry tree partly shaded the pool and later that summer when the fruit dropped the water turned a clear blood red. In the street below the garden wall I could hear the clip-clop of horse’s hooves on the cobbles pulling the gharries, or passenger carts. Occasionally there was the rumble of a car. As the water trickled gently over me, Dudley, Bill’s Siamese cat, padded past, and looked at me disapprovingly.

When I came from exploring the garden Khalil, the butler who had opened the door when we first arrived, appeared again with a big jug of pomegranate juice; it was a purply scarlet colour, like a dark ruby. The juice had been squeezed from the big glowing fruit I had noticed on a tree in the garden. I gulped it down; it was deliciously refreshing and became, especially when mixed with orange juice, one of the Damascus tastes I craved. I had yet to try what became my favourite juice in late summer, the intensely flavoured so called ‘black mulberry juice’ from the many mulberry trees in and around Damascus, which the cook also pressed from the fruits of the large mulberry tree beside the fountain outside my room.

Khalil was tall and thin with rippled black hair, shiny with hair oil, which contrasted with his light complexion; his neatly clipped moustache looked as if it might have been stuck on. He had worked for the British for many years, coming to work each day from the old Christian quarter of the city. He smiled at the way I drank the juice so eagerly, then took my hand and led me into the kitchen, where a wonderful and unfamiliar smell filled the room. The cook, Joseph, greeted me effusively; he was Armenian, quite podgy and pale, with a round friendly face and a rather incongruous bony nose. Enthusiastically, he showed me some lamb he was cooking for the evening meal.

…the memory of dishes produced in that kitchen proved to be my inspiration when I created my first recipes.

On the other side of the room a far larger, darker man was chopping fresh mint and grinding some spices with a rolling pin on a stone; the crushed mint and spices combined with the roasting lamb created a mouth-watering fusion of aromas. Khalil, who spoke good English and some French, told me that the huge man was the marmiton, which meant ‘cook’s boy’. I was astonished. I had never seen anyone less like a boy; his belly was enormous under a stained cook’s apron, he had bags under his eyes and a thick black moustache. His name was Mohammed, and he was twenty-four. Noticing my confused look, Mohammed laughed in a good-natured way and gave me a light, crispy little pastry, sticky with honey and tasting like perfume, and then popped two of them in his own mouth. This aromatic kitchen and the affectionate presence of Khalil, Joseph and Mohammed became an important part of my days in Damascus; many years later the memory of dishes produced in that kitchen proved to be my inspiration when I created my first recipes.

The next morning Shafiq dropped my mother and me near the main entrance to the al-Hamadiye souk in the centre of the old city. Holding hands, we walked into the dim light of what seemed like a vast arched corridor without end, full of mysterious sound and bustle. At the start of the 1950s the souk of Damascus must have looked very like it had done a hundred years before. Only the corrugated iron roof, punctured by bullet holes and held down by stones, dated from a more recent era when the French bombed Damascus in 1945, and the souk was machine-gunned from the air. The holes created thin shafts of sunlight, intensely bright in the darkness, which seemed to shoot down like a laser beam and pierce the ground as if they would burn a hole. The intensified light crisply illuminated parts of the shops on either side. The rich gold brocades, printed cottons and delicate vegetable dyed silks had not yet been replaced by man made fabrics in garish colours; there were no plastic objects, and almost no Western products. Dazzled by the jewellery shops I asked my mother if I was old enough to wear gold bangles on my wrist but she would only buy me a little dagger in a sheath made of silver filigree.

Most people in the souk still wore traditional clothes, and many of the men were in the long striped silk robes typical of Damascus. We saw groups of Bedouin tribesmen with their desert headgear: a large block-printed piece of cotton held by gold or silver rope and floating whites robes. My mother said they came from the desert to buy bridles, harnesses, camel gear, traditional tools and things for their goat hair tents. In spite of the summer heat they seemed to be stocking up for winter, buying sheepskin coats, thick woollen jackets and strong leather boots. Their boots came from the shoe souk, off the main corridor on one side, even darker and more crowded; I held my mother’s hand tighter. I had never seen so many shoes, slippers and sandals, some simple and some embossed with gold, even studded with bits of sparkling glass. Nor had I smelt leather quite like this, and was told that it was camel leather. In the close atmosphere the smell was quite overpowering; I was relieved when we reached the sweetmeat shops with their pointed mountains of succulent crystallised fruit.

Perhaps the most exciting moment was when we entered the part of the souk devoted to spices. I could not believe that these vast bowls of many coloured powders, seeds and pieces of bark, nor the incredible scent which came from them, could have anything to do with food, but I was intrigued by them, and thanks to Joseph’s skill in our kitchen I was soon converted to the kind of dishes that few little English children would have accepted. That introduction to the magical world of spices in the Damascus souk was the start of a lifetime of visits to spice markets wherever I go, and led me to use spices with confidence as soon as I started cooking myself, by trial and error; in the very first dish I ever attempted, a shepherd’s pie in the tiny kitchen of my shared student flat in south London, I could not resist adding a little ground coriander and a few cumin seeds.

Soon I met several families from the small British community at the first of many picnics in the Ghouta, the oasis that encircled Damascus. In fact the city was still so small that at night we could hear wolves howling in the desert beyond the oasis and you could walk from the centre to the edge of the Ghouta in ten minutes. Irrigated by streams that filtered out from the Barada, the oasis was a gentle haven between the busy city and the harsh desert on the other side. Little paths connected the orchards where there were almonds, olives, walnuts, pomegranates, vines climbing through the trees, and all kinds of fruit trees. Above all there were apricots, to this day the most delicious apricots I have ever eaten. A local saying was ‘Bukra til Mish-Mish’, which means roughly, ‘See you tomorrow under the apricots’. In a turbulent land the Ghouta was truly an idyll of peace.

Bill heard that a large stone house in the cooler mountains, about fifty kilometres above Damascus, just outside the village of Bloudan, still belonged to the British. In the early 19th century a British consul, Richard Wood, had acquired it to use as summer quarters for British consuls and their families. But since the most famous British consul, the legendary Richard Burton and his wife Isabel, made it their summer quarters in the early 1870s it had not been inhabited. Bill persuaded the Foreign Office to let us use it when his older children from his first marriage came out for their school holidays. It was very shabby and sparsely furnished but new mattresses were found for the rickety bedsteads, walls were whitewashed and my mother bought cotton in the souk with a design of tiny Damas roses, which was made into simple curtains.

It was not luxurious but we spent most of the time outside. We ate well, as Joseph came up with us to cook. Although the rooms were Spartan the house had a large garden with a stream running through it, and spectacular views over six mountain ranges. There were several walnut trees and even an old croquet lawn, a game that Bill loved, specially cheating at. The air was far cooler than in Damascus and incredibly clear; the sky a deep flawless blue by day, seemingly impenetrable, like a dome which at night became an intense blue black, densely sparkling with sharply defined stars.

But it was not silent in the mountains; during the day there was a constant hee-hawing of donkeys and as soon as it was dark a loud chorus of frogs would start up in the stream at the bottom of the garden. This reminded Bill how delicious frogs’ legs were. He made a hole in the mud wall on the far side of the stream, chased frogs into it, then put his hand in and pulled the struggling creatures out, flinging them into a sack. Poor Joseph had the job of cutting the little things in half. At one meal seven of us consumed more than fifty pairs of frogs’ legs.

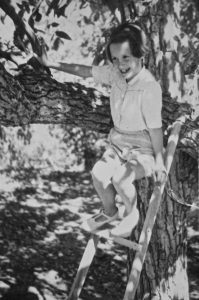

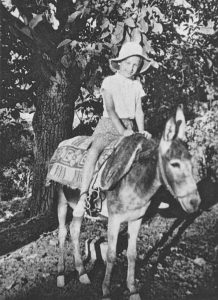

My stepsister and I were lent two donkeys which we used to ride, accompanied by someone we called ‘the donkey boy’, on a track up the mountain behind to the ‘swimming pool’ of Dr Kahil, a local doctor. In reality the pool was a fairly small but deep stone reservoir full of dark, cold water. It was shaded by a large fig tree laden with light green figs that were like soft little bags of pink honey filled with crunchy seeds; one of the branches of the tree hung so far over the water that we used to pick the figs while we swam and eat them in the water. I remember it as a blissful experience.

Once, on our return to the house, the donkey boy suddenly fell to the ground, jerking alarmingly and frothing at the mouth. Joseph rushed out of the house with a large kitchen knife. He took the boy’s head in his hands and thrust the knife into the ground just above it. At this point my governess appeared and tore the knife from the ground, shouting angrily at Joseph. The poor boy, who we later learnt was an epileptic, came round to the sound of Joseph shouting back at Mrs Rydon; the knife had been put in to ward off the evil spirits who were attacking the boy, he told her, and pulling it out was sacrilegious and would bring terrible bad luck. Mrs Rydon looked mortified and retired to her room for the rest of the day.

Six months after our arrival in Damascus, my half-brother Matthew was born in the Victoria Hospital, an old missionary hospital not far from our house. The Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society opened the Victoria Hospital in Damascus in 1897, the Diamond Jubilee year of Queen Victoria’s reign. Dr Emrys Cadwaladr Thomas, who became Superintendent of the hospital in 1933, was an exceptional man and a clever doctor who spoke with a strong Welsh accent and had a great sense of humour. When the Vichy French took over the city in 1940 he had to flee from Damascus dressed as an Arab. Loyal Syrian friends took all the movable equipment from the hospital, hid it in villages in the area and themselves guarded the hospital building.

By 1945 Dr Thomas was back at the hospital when Damascus was bombed yet again by the French; he and his team took in four hundred casualties within a few hours. The bombing and the machine-gunning continued for three days and nights without cease before the British intervened and evacuated the French forces. Throughout the following turbulent years of continuous political changes and dangers Dr Thomas and his wife remained at the hospital. By the start of the 1950s the building was in a sadly dilapidated state and Dr Thomas admitted that it had not been possible to keep up with progress; the Victoria was put to shame by modern hospitals, such as the University Hospital nearby. But what never changed was the efficient and affectionate care of the nursing staff. Dr Thomas’s wife Peggy was praised particularly for her skilled nursing of mothers and babies, and when my mother was pregnant again, two years after the happy experience of Matthew’s birth, she planned to go there again. However, about a month before my mother was due to have her baby, in the middle of a formal dinner party, she haemorrhaged; blood soon covered the seat of her chair and trickled down onto the marble floor as the guests looked on in horror. She was rushed to the Victoria Hospital but was very weak from loss of blood by the time she got there. Dr Thomas told Bill that the only way they could hope to save either her life or the baby’s would be to perform a Caesarean section. What Bill did not know was that this operation had never been done at the hospital before and that the only anaesthetic was a cloth soaked in chloroform that my mother had to inhale. However, the operation was rapid, my mother was alive and a girl was born, who cried strongly. Despite the lack of an incubator everyone was hopeful. But the next morning Bill found my mother, exhausted and distressed, holding the tiny infant in her arms and trying, again and again, to feed her with drops of milk from a fountain pen, though the baby seemed too weak to swallow. Towards evening the baby died in my mother’s arms. That was the moment, she told me in her old age, which she could never forget, when she felt the warmth leave the little body so quickly.

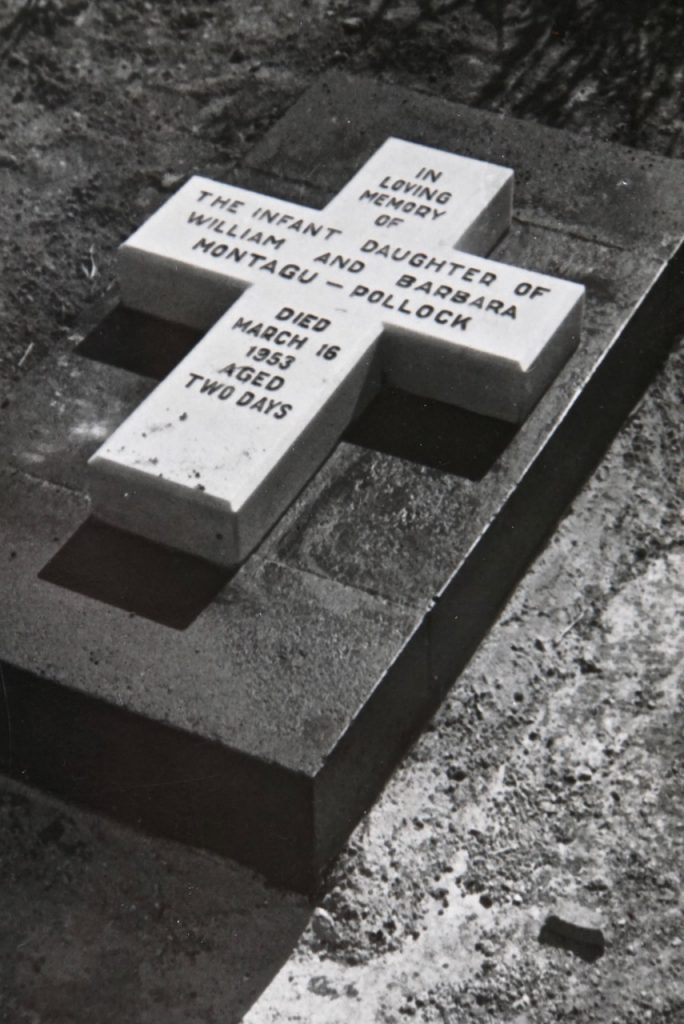

The death of Barbara’s baby touched everyone in the closely-knit ex-pat community in Damascus. Bill was seen carrying a small white coffin out of the Victoria Hospital and putting it onto the back seat of the embassy car. Shafiq drove to the old Protestant Cemetery just outside the city walls. Harold Adkins, the Anglican chaplin, wearing his gown and surplice, was waiting among dusty tombstones, many of them the sad little graves of babies and young children from missionary families. He conducted a short service and the baby was buried near to the impressive tomb of the famous adventuress Lady Jane Digby, who had married a Bedouin sheikh. My mother was still in hospital, too weak to be there.

My mother never got over the death of her baby; during the last two mentally confused years of her life she used to talk often of ‘the baby’ and ask me to fetch it from the next room. After she died I thought about my infant sister still buried in Damascus, unvisited and forgotten. I thought about the happy years there before the tragedy had clouded my mother’s life, and I wanted to return, to try and find the house we had all loved; even the Foreign Office did not know if it still existed. Above all, for my mother, I felt I must visit the baby’s grave.

In October 1998 I flew to Damascus and arrived late at night. The hotel I had booked was the faded Art Deco Omar Khayyam on Merji, or Martyrs Square, which I knew was in the Halbouny district where we had lived. In 1950 there were still weekly public hangings of thieves, murderers and sometimes Israelis in this square. Crowds would watch the hangings at dawn, and the bodies, with placards round their necks stating their crimes, were left hanging until they were cut down at noon. I remembered the astonishment on my mother’s face when our chauffeur Shafiq asked her if he could take me to see the hangings, and his look of puzzled surprise when she firmly replied that it was out of the question.

When I walked out of the hotel next morning I could see how shabby this once fashionable area had become; all the expensive houses, flats and diplomatic residences have been in the constantly expanding modern parts of the city for decades. But as soon as I started walking down University Street it felt familiar, and I knew it was close. Then on my left, behind a wall, I saw something that made my heart miss a beat. It was a ruin, yet quite unmistakably it was ‘our’ house. I was told that sixteen years before someone had bought it and started to demolish it for development, but because of a squabble over the ownership of the land the work have stopped. So there the half-ruined house still stood, with the familiar wide staircase now leading to a non-existent upper floor, in a large area of parched wasteland, the devastated remains of our lovely garden.

I felt comfortingly at home. Even in its dying state I found the house welcoming.

The strangest thing about returning to the ruin of our house, which could have been such an upsetting reminder of a lost and enchanted time, was that I didn’t feel sad. Instead I felt comfortingly at home. Even in its dying state I found the house welcoming. The street and surroundings, although so changed, gave me a feeling of security. A small part of me imagined that I had experienced no other life, had never grown up, and that if, standing her on the street that sunny morning, I shut my eyes and opened them again the house would be just as it used to be; the ruin would have been a dream.

The old Protestant cemetery in Damascus is now unromantically sandwiched between two main roads leading to and from the airport. It was easy to find the prominent tomb of Lady Jane Digby, who died in 1881. And a few feet away, placed flat on the ground, was the simple marble cross that my mother and Bill had chosen for their lost child. Above my head branches of a pink peppercorn tree, with its feathery leaves, gave the graves a delicate lacy shade in this bleak and sun-scorched corner of Damascus. Nearby I noticed a little boy of about ten years old, holding a hosepipe. I asked him if he could wash the thick dust and dirt from the marble cross so that the words could be read once more. He sprayed water on the marble and then rubbed it with an old cloth. Gradually the words, tarnished brass set in the marble, appeared:

In loving memory

of the infant daughter of

William and Barbara Montagu-Pollock

Died March 16th 1953

Aged two days

I felt that at least I had done something for the tiny baby who had lain alone in this distant place for so long, for the sister I had never known, and for our mother.

Josceline Dimbleby was brought up both abroad and in England.

Author and Food Writer

She has been one of Britain’s most popular food writers for over thirty years.